Griffith Stadium is packed for a doubleheader between the Washington Senators and the New York Yankees. The two teams are battling for first place, and the atmosphere at the stadium, located in the heart of Washington's black community, is electric. In the first game, while chasing a foul ball off the bat of Senators first baseman Joe Judge, Yankees legend Babe Ruth knocks himself unconscious running into the right-field retaining wall--directly in front of the pavilion reserved for the Senators' black fans.

Griffith Stadium is packed for a doubleheader between the Washington Senators and the New York Yankees. The two teams are battling for first place, and the atmosphere at the stadium, located in the heart of Washington's black community, is electric. In the first game, while chasing a foul ball off the bat of Senators first baseman Joe Judge, Yankees legend Babe Ruth knocks himself unconscious running into the right-field retaining wall--directly in front of the pavilion reserved for the Senators' black fans.A photographer perched in foul territory captures a classic image of the black fans peering down at the sprawled-out slugger. Trainers rush from both dugouts with water buckets and black medical bags. Players from both teams look on anxiously. Police Captain Doyle, a caricature of an Irish cop, stretches out a white hand to keep a sea of black faces at bay.

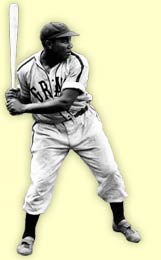

Buck Leonard, a husky, sixteen-year-old railroad worker, almost certainly stands among the multitude of concerned fans. A future Negro League star, Leonard is attending his first major league baseball game. Sam Lacy, an eighteen-year-old stadium vendor and future sportswriter, is selling soft drinks and making comparisons between the white players in major league baseball and the black players in the Negro Leagues whose teams play at Griffith Stadium when the Senators are out of town. Two decades later, Leonard emerges as the star first baseman of the Homestead Grays, Lacy as a crusading black journalist actively campaigning for the integration of major league baseball, and the Grays as the best baseball team, black or white, playing at Griffith Stadium.

In 1940, seventeen years before the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles and the Giants moved to San Francisco, the greatest baseball dynasty that most people had never heard of moved the bulk of its home games from Pittsburgh to Washington, D.C. Behind their home-run hitting catcher Josh Gibson and slugging first baseman Buck Leonard, the Homestead Grays dominated black professional baseball, known as the Negro Leagues, by capturing eight of nine Negro National League titles from 1937 to 1945. Historians dubbed Gibson the "Black Babe Ruth" and Leonard the "Black Lou Gehrig" and compared the Grays to the great New York Yankees teams of the 1920s and '30s.

Although the Grays originated in the steel town of Homestead, Pennsylvania, they reached the peak of their popularity by playing their home games at Washington's Griffith Stadium. From 1940 to 1950, the Grays played at Griffith Stadium when the Washington Senators--one of the worst teams in the major leagues during that period--were out of town. The Grays outclassed the Senators (also known as the Nationals or, as headline writers often referred to them, the Nats) on the field and often outdrew them at the box office. When sportswriter Charley Dryden quipped that Washington was "first in war, first in peace, and last in the American League," he wasn't referring to the Grays. During World War II, the Grays fielded one of the best professional baseball teams of any color, capturing Negro National League titles and competing against Satchel Paige and the Kansas City Monarchs in showdowns that electrified Griffith Stadium the way Ruth's Yankees once did. The big difference was that nearly all the fans at Grays games were black.

During the first half of the twentieth century, Washington, D.C., was a segregated Southern town. Racial discrimination in the nation's capital prevented blacks and whites from attending the same schools, living on the same streets, eating in the same restaurants, shopping in the same stores, playing on the same playgrounds, and frequenting the same movie theaters. As a result, black and white Washingtonians lived in separate social worlds.

Those worlds collided at Senators games. Griffith Stadium was one of the few outdoor places in segregated Washington where blacks could enjoy themselves with whites. The ballpark, located at Seventh Street and Florida Avenue in northwest Washington, stood in the heart of a thriving black residential and commercial district. It also was just down the street from Howard University, the "Capstone of Negro Education." The educational opportunities at Howard and the job opportunities in the federal government had lured many of the country's best and brightest black residents to the nation's capital. Many of them lived near the ballpark in neighborhoods such as LeDroit Park, which was just beyond Griffith Stadium's right-field wall.

With an affluent black population in their own backyard, the Senators boasted one of major league baseball's largest and most loyal black fan bases. The Senators' black fans sat in the right-field pavilion--Griffith Stadium was one of only two segregated major league ballparks (Sportsman's Park in St. Louis was the other). Segregated seating, however, did not deter the Senators' black fans from attending games. On the contrary, black Washingtonians were so enamored of the Senators that they refused to support any of the Negro League teams that played at Griffith Stadium during the 1920s and 1930s. The Senators enjoyed unprecedented success during this period--winning the World Series in 1924 and returning to the Fall Classic in 1925 and 1933--as well as unwavering support from their black fans.

Only one player during the 1920s and '30s tested the loyalty of the Senators' black fans--Babe Ruth. The Babe's big lips and broad, flat nose often triggered racial epithets from white players and fans but endeared him to black ones. "Ruth was called 'nigger' so often that many people assumed that he was indeed partly black and that at some point in time he, or an immediate ancestor, had managed to cross the color line," wrote Ruth biographer Robert W. Creamer. "Even players in the Negro baseball leagues that flourished then believed this and generally wished the Babe, whom they considered a secret brother, well in his conquest of white baseball."

With their "secret brother's" retirement in 1935 and the Senators' nosedive after the 1933 season, the calls for a "real brother" on the Senators came from the team's black fans. One of those fans was a Washington native and young journalist named Sam Lacy. During the mid-1930s, Lacy began lobbying Senators owner Clark Griffith to integrate his team. But from Ruth's retirement until Jackie Robinson's debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, Lacy and other black Washingtonians waited in vain for another major league hero.

During World War II, the Homestead Grays ended the long-standing love affair between black Washingtonians and the Senators. Blacks flocked to Grays games, not out of some social obligation but because they thirsted for recreational outlets during the war and they loved good baseball. While such major league stars as Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Hank Greenberg, and the Senators' Cecil Travis were off serving in the military, the Grays maintained a team of talented yet aging players led by Gibson and Leonard. Satchel Paige, the star pitcher for the Kansas City Monarchs, also was too old to serve in the military, but not too old to compete. The Grays-Monarchs clashes were the best show in town. Although white fans never caught on, more than twenty-eight thousand black fans attended a 1942 Grays-Monarchs game at Griffith Stadium. They sat wherever they wanted. And they saw top-notch professional baseball.

The Grays' popularity and on-field success transformed Washington into the front lines of the campaign to integrate major league baseball. The city was a natural forum for social protest. Segregation thrived in the nation's capital while the United States fought a war against Nazi white supremacy. The city's sophisticated black population was ready to embrace a black major league player. The best team in the Negro Leagues played in the same ballpark as one of the worst teams in the major leagues, highlighting the illogic of maintaining separate leagues. And no major league team was more desperate for an influx of new talent than the Senators, who could have been instant contenders by signing Grays sluggers Gibson and Leonard.

Recognizing all of these factors in Washington's favor, Lacy and other black journalists initially thought that the best chance of integrating the major leagues lay with Griffith. As a young manager with the 1911 Cincinnati Reds, Griffith had pioneered the passing of olive-skinned Cubans as "white" major leaguers. As the owner of the Senators, he continued his practice of plucking players out of Cuba with the help of his primary scout, Joe Cambria. Griffith also forged a healthy relationship with Washington's black community and encouraged the development of the Negro Leagues. The Senators owner, however, was set in his ways, and he made so much money by renting his ballpark to the Grays that he refused to sign Gibson and Leonard. Griffith also had a secret ally--Grays owner Cum Posey--in maintaining separate leagues. Over time, Griffith became one of the most outspoken supporters of segregation.

Two leading black sports columnists, Lacy of the Baltimore Afro-American and Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier, made Washington, D.C., one of the focal points of their efforts to integrate baseball and Griffith the target of their most biting criticism. Had it been up to Lacy, blacks would have played on the Senators closer to Ruth's time than to Robinson's.

This is the story of the lost era between the Babe and Jackie, of a crusading journalist named Sam Lacy, an immensely talented black ballplayer named Buck Leonard, and a stubborn major league owner named Clark Griffith. It's the story of why the fight to integrate major league baseball began in Washington and not in Brooklyn, why black Washington ultimately lost the fight, and why the Senators were not the first team to integrate. And it's the story of the greatest baseball dynasty that most people have never heard of, the Homestead Grays, whose wartime popularity at Griffith Stadium moved them beyond the shadow of the Senators.

Copyright © 2003 by Brad Snyder. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted by the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Photo Credits: Josh Gibson - Art Carter Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University. Buck Leonard with fans - Smithsonian.